AUSTIN, Texas-If you should need a list of 638 personality traits, 58 ways

in which elephants resemble stars or 45,540 what-if questions about toxins,

Patrick Gunkel is your man.

AUSTIN, Texas-If you should need a list of 638 personality traits, 58 ways

in which elephants resemble stars or 45,540 what-if questions about toxins,

Patrick Gunkel is your man.

Mr. Gunkel is inventing a new field, which he calls ideonomy. Simply described, it is a computerized spinning of ideas. But Mr. Gunkel defines it in grander terms-as nothing less than "the science of the laws of ideas and of the application of such laws to the generation of all possible ideas in connection with any subject, idea or thing." All ideas? On anything? Mr. Gunkel often sounds so far out, one doesn't know quite what to make of him. But his notions intrigue just about everyone who knows of them. "He has provocative ideas on artificial intelligence," says Edward Fredkin, the former director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's computer science laboratory. "He has encyclopedic scope," says Frederick Seitz, the president emeritus of Rockefeller University. Adds Robert Clark, a Harvard University law professor, "Gunkel is undoubtedly the most interesting person I've ever met." The 40-year-old Mr. Gunkel flunked out of high school and never attended college. But supported by occasional research grants, he has wandered for 20 years among universities and think tanks, following his nose from subject to subject and acquiring an astonishing breadth of knowledge. Ask him about black holes, economic cycles or pigs with wings, and he will discourse on the subject at length. He has recorded all this learning in the form of lists.

In fact, heaps of them litter his apartment here. There are lists of odors, newly coined words, diseases and brain functions. There are lists of analogies, archetypal shapes and lists of other lists. Mr. Gunkel sometimes even speaks in rapid-fire lists: "With ideonomy, we can design new kinds of clothing, textures, political systems, sports! Flowers! Dogs! Dance movements!" If asked, he will reel off the 14 kinds of soda pop he has on hand.

Lists are the raw material of ideonomy. Weaving them together in a personal

computer, Mr. Gunkel attempts to replicate, in some sense, what happens

when, in a flash, human minds make connections.

Combining lists of objects' sizes, for example, he invented an educational

game based on such analogies as this: "A blood cell is to a pea as an oil

tanker is to the atmosphere." For another mind game, he combined lists

of personality traits and emotions in order to generate 84,496 two-word

descriptions of psychological states, such as "arrogant affection," "practical

hostility" and "insecure acceptance." Many of the phrases are senseless,

he says, but ones that click on a fast reading can suggest new insights

about people.

Such simple "idea combinatorics," as Mr. Gunkel calls this matchmaking,

is just a playful warming up for ideonomy's more serious goal of suggesting

insights to scientists and other researchers. Mixing lists of natural phenomena

and fallacies, for instance, he generates reams of questions, such as "Can

arteries have rashes?"

Most of them are gibberish-except to someone as wildly imaginative as Mr. Gunkel, who once wrote several thousand words on fallacies about ant slavery. But occasionally his method hits the eureka button. Combing through Mr. Gunkel's printouts, a visitor recently stumbled onto the question, "What are the structural irregularities of superconductors?" Independently of ideonomy, this question recently became a hot topic among physicists studying new materials that conduct electricity without resistance. But can arteries have rashes? When recently visiting Mr. Gunkel, Austin pathologist Michael T. O'Brien was faced with that question. "At first, I thought it was nonsense," he says. But on reflection, he remembered that, like skin, some large arteries are supplied with blood by tiny vessels. Then, he realized that such vessels might indeed become inflamed and dilated, as do those in the skin.

"I don't know whether something like this makes any difference in a disease or not," says Dr. O'Brien. "But it seems like something somebody should be researching." Though ideonomy seems surprising-or downright bizarre -- to the uninitiated, it has plenty of precedents, says Mr. Gunkel, pulling out a list of them from one of his stacks. In the 19th century, for example, the British philologist Peter Roget devised a kind of universal idea map as part of his well-known thesaurus. And the periodic table found in any high-school chemistry book, says Mr. Gunkel, shows how combining lists-of families of elements, in this case- can reveal previously unseen connections. Mr. Gunkel recalls that he first began thinking ideonomically when, as a child, he visited Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry and had a religious experience with all the diagrams, graphs, meters and audio recordings he encountered there. In his teens, he discovered Joyce's "Finnegans Wake," the ultimate novel of hidden connections. "It has 16 levels of puns!" he marvels. Soon after that, he blasted off into intellectual outer space, leaving behind such mundane concerns as schoolwork, jobs, marriage, eating and sleeping. In rapid succession, he failed as a student, mailman and park-maintenance man. Even the Army found him unfit. When drafted, "I just pretended to be myself, and they thought I was nuts," he says, emitting staccato barks that sound uncannily like a list of laughs. Meanwhile, he was researching and writing books -- 16 so far, all of them unpublished-on everything from the science of sidewalks to theories about the brain. Occasionally, he would materialize without warning in the offices of various luminaries, spouting ideas with the fervor of a boy scientist who has just produced dynamite in the basement.

That's how he met MIT's Mr. Fredkin, who, ironically, was discussing misunderstood geniuses with colleague Marvin Minsky one day in the early 1970s when Mr. Gunkel barged in. With his rail-thin build, manic gestures and torrential ideas, the young stranger "seemed to be a living example of what we were talking about," recalls Mr. Fredkin, who soon brought him to the school for a two-year research stint. The late Herman Kahn, a co-founder of the Hudson Institute, met Mr. Gunkel under similar circumstances and reportedly hired him after their first rap session. Over the years, a trickle of money from such friends has been Mr. Gunkel's life-support system as he has explored the distant planet of his own mind.

That voyage has left him little time to socialize, a part of life that he cheerfully says is "totally mysterious to me." But after 15 years of reading, writing and ranting in Boston's academic circles, Mr. Gunkel last year moved to Austin in search of more sun and new friends. To find them, he pored over the University of Texas phone book, made a list of 52 students and faculty members living near his apartment and went knocking on doors. Introducing himself is a snap, he says: "I just show them one of my lists." Meanwhile, he is beginning to write his magnum opus on ideonomy, a project financed by a five-year unsolicited grant he was awarded in 1984 from New York's Richard Lounsbery Foundation, a nonprofit supporter of research. The $20,000-a-year grant, like most of Mr. Gunkel's awards through the years, was arranged by academic friends who regard him as the ultimate long shot-one that just might pay off big.

The jury is still out on ideonomy. But it already has helped some researchers.

Ideonomical analogs, says Mr. Clark, the Harvard law professor, helped

inspire him to write a research paper comparing the structure of plants

with human hierarchies. And a Gunkel list enumerating mistakes that people

make may help in the design of artificial-intelligence systems that can

recognize and correct their own mistakes, says Douglas Lenat, a researcher

at Microelectronics & Computer Technology Corp., a high-tech consortium

in Austin. But can there really be a science of ideas? Even Mr.

Gunkel isn't quite sure whether the notion is bonkers or brilliant. And

even if it is possible, it might be too unwieldy to be practical. Indeed,

brainstorming with Mr. Gunkel is a bit like being hit over the head

by the muse with a sledgehammer. "He puts people off," says Mr. Lenat.

To help a biologist interested in toxins, Mr. Gunkel within minutes had

his computer generate 45,540 questions on the topic. Paid a penny for each

of the interesting thoughts he is producing, Mr. Gunkel might someday be

a millionaire. "He pours out about 60 ideas a minute, and 59 of them

are bad," says Mr. Fredkin. "But even with one good idea out of 60, it's

still an amazing accomplishment."

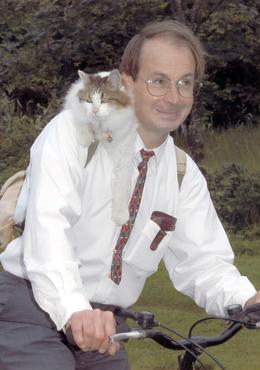

Except for an expression of wild excitement in his eyes as he expounds on his topic, Patrick Gunkel's appearance - slender build, pale complexion, brown hair, glasses - is not exceptional. But this man is working on a grandiose idea, one he fervently believes has the power to unleash a revolution. The Austin newcomer claims that if he succeeds in establishing ideonomy, the new science he is inventing, the history of the world will be divided into pre-ideonomy and post-ideonomy eras!

....Robert Clark, a Harvard law professor who has known Gunkel since he was a teenager, says.... Gunkel is "the most interesting man I've ever known," a phrase that is almost a cliche amongst those who have had the experience of knowing Gunkel Edward Fredkin, former director of the computer science laboratory at MIT, predicts that Gunkel will "someday be recognized as a significant personality of this era." Charles Van Doren, former vice president of product development at the Encyclopaedia Britannica, declares that Gunkel is the "prophet of a new science that is absolutely mind-boggling in its possibilities."

Even the definition of the new field that Gunkel reels off is mind-boggling- "the science of the laws of ideas and the application of such laws to the generation of all possible ideas in connection with any subject, idea, or thing." Gunkel elaborates: "The world of ideas is a real thing - I call it the ideocosm. Within that world there is an infinitely complex structure of relationships, which are not just descriptive, but regulatory, like the laws of physics. The purpose of studying these laws is to explore, manipulate, and generate ideas in connection with any subject, problem, phenomenon, or possibility. Ideonomy is concerned with the qualitative aspects of nature in the way that mathematics is concerned with the quantitative aspects."

Currently in his fourth year of a five-year grant from the Richard Lounsbery Foundation in New York to found ideonomy, Gunkel moved from Boston to Austin last year in search of the "warm climate and warm people of Texas."

With the help of Bruce Porter, professor of computer science, and Ronald Wyllys, dean of the graduate school of Library and Information Science, Gunkel has been appointed Visiting Scholar at UT and given access to the university's libraries and other facilities. Says Wyllys, "We feel we can offer Gunkel some help in his research and I'm confident that this association will benefit the university and make it even more famous than it already is."

A desire to be near the university, surrounded by eminent scholars in

a variety of fields, was another reason for Gunkel's choice of Austin.

He considers explaining to scholars how ideonomy can revolutionize their

fields and asking for their feedback an essential part of his work.

He can often be

seen emerging from a taxi near campus. (He no longer maintains

a car or driver's license, because of his tendency to drive in a straight

line as he contemplates a less concrete world.) Lugging around with

him a four-foot case of charts and lists, he drops in on professors uninvited.

Reactions to his

visits vary but - it is safe to say - always include amazement.

Gunkel explains that as the world's first ideonomist, one of his

primary tasks is to work out a taxonomy of ideas, just as biologists, in

order to create a true science, had to classify all plants and animals

into phylum, class, genus, and species. Gunkel has begun by dividing

ideas into 320

categories, or divisions. The divisions are an astonishing mixture

of familiar terms (Abilities, Analogies, Assumptions, Behaviors, Beliefs,

Causes, Complexities, Conflicts, Convergences, Criticisms, Cycles); coined

terms (Anadescriptions, Holomorphoses, Interknowledges, Panintertransformations);

and terms that are just plain bewildering in this context (Bads, Leftovers,

Rosetta Stones, Things, Trees).

"The next thing you can do," Gunkel explains, "is plot the divisions against each other. For example, Trees is a division and Inequalities is a division, so you can have Trees of Inequalities or Inequalities of Trees, two different things. The intersection could suggest new fields of research that might be developed. In this case, it turns out that the fields already exist.

Inequalities is an important subfield of math and so are trees, in terms of graph theory. There are trees of inequalities as well."

Gunkel states that intersections can go on in this way, cross-breeding

ideas and expanding exponentially. Since crossing just the first

level of 320 divisions by each other would yield 102,400 lists, and each

cross then calls for a hierarchy of countless other lists, Gunkel is concentrating

on a few

sample divisions for later ideonomists to imitate. Of course

computers will be necessary for combining the lists to the third, fourth,

and n-th dimensions, he replies to the obvious question. "In fact,

it is almost impossible to imagine ideonomy without computers. What

you can do is dump

lists on the computer and it forms a matrix of idea spaces. With

use, the idea spaces would grow and throw out rays, and before long all

these interconnections and paths and relationships would form, and you

could move around in an infinite hierarchy of spaces. My own limitations

of time, funds,

and expertise have only allowed me to scratch the surface of computers'

role in ideonomy."

To give us a sample of how ideonomy works, Gunkel rummages through the

mountains of lists, charts, and computer printouts that crowd his south

Austin apartment. He tosses out chart after chart relating to one

of his "favorite guys," Illusions. There are Reasons for Studying

Illusions; Principles for

Studying Illusions; Dimensions of Illusions; Causes, Origins,

and Bases of Illusions; Consequences of Illusions; Principles

of Illusions; General Examples of Known and Speculative Illusions;

Previously Shattered Illusions in the Sciences; and Illusions Regarding

Time, Space, and a Stone.

Gunkel pauses to explain the last title. "I chose a stone because

it's so seemingly trivial, yet there are some interesting illusions in

connection with it." He sets a large color-coded chart against a

chair. "Here I reproduced the 35 illusions about a stone, and

going across I listed 11 other things that

might be similar to a stone, like a soil particle, an asteroid, the

moon, a brick, a mountain, a human tooth, and all of nature.

The point is to see whether the illusions about a stone have a tendency

to carry over to similar things." He reads the first item from the

list: "'Absolutely lifeless.'

Well, one kind of stone where that might be an illusion is manganese

nodules, which exist by the quadrillions in the oceans. It's

known that they grow but we don't know why. If 'absolutely lifeless'

is an illusion, we can hypothesize that there's an associated organism

of some sort - perhaps algae

or bacteria. Similarly, carrying over the 'absolutely lifeless'

illusion to a soil particle suggests there might be organisms associated

with that. We could go out to find these organisms and modify them

to improve the soil for more efficient agriculture. What you might

do is modify organisms differently

in different layers. LAYERS by the way is another division of

ideonomy. In the upper soil layers . . ."

Eventually Gunkel gets to the second item on the chart of illusions regarding a stone: "solid." "Of course," he declares, "it's an illusion that any matter is solid. We know that if you go down to the nucleon level, the stone is at most 1 part in 300 trillion full." Gunkel goes on spinning out ideas like this at a dizzying pace. And we're only on the second item of the 35 illusions regarding a stone!

If we are bored with illusions, we can poke around in Gunkel's stacks and come across such lists as, Types of Odors (235 items), Elementary Generic Assumptions (230 items), Ways that Elephants Resemble Stars (58), Types of Causes (250), Personality Traits (638), Universal Shapes (230), Primary Types of Order (74). Computer printouts record the combinations of lists, such as 17,020 Possible Shapes of Order, and 45,540 Questions about Toxins!

Lest you conclude that lists and their combinations are the essence

of ideonomy, Gunkel asserts that lists are simply a tool for manipulating

ideas, just as equations are a tool of mathematics. "The real essence

of ideonomy is to systematically transcend our usual narrow way of looking

at things, to

train the mind to a universal viewpoint. Ideonomy is needed because

the way science is done today is moronic. The way a moron looks at

something is to see a little isolated part with no larger significance.

Instead, every time we discover something, it should in turn open up 10,000

other things. For example . . . "

Gunkel himself may be the best example of what ideonomy can do. His ideas seem to flow out in an accelerated time scale, bytes-per-nanosecond perhaps. You want to shout, "Stop, that sounds interesting. Let me grasp it before you go on."

Betsey Dyer, a microbiologist on the faculty of Wheaton College, in

Norton, Massachusetts, says you need to develop a technique to listen to

Gunkel. "He generates ideas so fast you need a giant sieve to catch

them, analyze them, and decide what to do with them. With some of

the ideas, you can nod and say, 'Yes, that's true.' With others,

you say, 'Gee, I don't know if that happens, but if it does, it would be

amazing - and important to research.' Some of the ideas can sound

so far-fetched the first time you hear them. You have to keep the

right amount of being open and being critical. It really takes a

different mind-set to think ideonomically. I'm getting better

at it."

Dyer continues, "I was working recently on a theoretical paper on neuron function that gets back to the early evolution of bacteria. It happened to be the day that Patrick was thinking about electronics. He has days when he thinks about different fields like that. He told me to go to the library and get a book on electronics. I couldn't understand why. But I did and it worked! On the basis of that, I came up with an absolutely brilliant idea. If my paper is published, I'll have a footnote saying, 'Idea generated by Pat Gunkel, ideonomist.' "

Gunkel is the first to admit that thinking ideonomically is not new.

"In a sort of model-T sense," Gunkel says, "ideonomy is active already.

For example, people have been thinking by analogy since the beginning of

history. What is needed is to bring these thought processes out and make

them

conscious, explicit, and exponentially more active."

He has a list - naturally - of those who preceded him in formally classifying

ideas in some sense or other, including Leibniz, the 17th century philosopher;

Roget, the inventor of the thesaurus; and Mendeleyev, the discoverer of

the periodic table. Gunkel awards the title of "grandfather of

ideonomy" to the late Caltech astrophysicist Fritz Zwicky. The

famous scientist really went into astronomy as a way of doing "morphological

research, his name for ideonomy," says Gunkel. "But no one until

now has worked out the details of how a whole science of ideas would work."

The self-appointed founder of this science has no academic credentials - not even a high school diploma! - but has spent most of his forty years in a lofty intellectual realm of his own making. A child prodigy who later studied and worked with child prodigies, Gunkel was unable to conform in the classroom and had one of the lowest grade-point averages in his class at a suburban Chicago high school. His teachers didn't take kindly to his habit of checking all the choices in multiple choice questions, and then adding a dozen or so more in the margins!

Escaping to the library, however, Gunkel devoured books by the likes of Rabelais, James Joyce, and Alfred North Whitehead, as well as encyclopedias, and books on science and technology. The teen-aged Gunkel was soon writing his own personal books of poetry, philosophy, and science.

Gunkel soon dropped out of high school and got a job as a mailman. Spending most of his income on books and journals, he set himself the goal of reading one scholarly book a day for an entire year. "I decided to turn myself into an intellectual machine, to think as clearly and comprehensively as humanly possible," Gunkel says. Feeling that he had a special mission to use this knowledge to contribute to the world, Gunkel wrote a book about demography and another about the evolution of the city, but never tried to get them published. When called to serve in the army during the Viet Nam war, Gunkel complained to his draft board that he had "more important things to do for society." The board didn't agree. But it took Gunkel only seven days to make himself such a nuisance that the army was happy to discharge him!

During his studies, Gunkel developed a keen interest in the future,

a special interest also of the late Herman Kahn, who was co-founder of

the Hudson Institute, a New York think tank. In 1969, at the age

of 21, Gunkel dropped in on Kahn one day. After that single chat,

Kahn reportedly hired

Gunkel to do futurology studies. A CATALOG OF FUTURAL IDEAS,

a three-volume work that attempted to summarize the entire literature on

the future, was the result.

That work led to negotiations amongst Gunkel, the Encyclopaedia Britannica, and the Walt Disney Corporation on a paradoxical idea: the production of an encyclopedia of the future. But the improbable trio were never able to agree on plans for the project, and the deal fell through. Gunkel now says the idea was premature, but would be feasible with today's computer modeling.

Another formidable Gunkel project began one day in 1971, when he barged

in on MIT's Fredkin and renowned artificial intelligence pioneer Marvin

Minsky just as they happened to be discussing misunderstood geniuses.

Gunkel seemed to be "a living example of what we were talking about," recalls

Fredkin. Later Gunkel sent Fredkin a lengthy, unsolicited list of

pros and cons of the

development of artificial intelligence. In response, Fredkin

sent the high school dropout a check for $200 and an offer of a research

position at the MIT computer science laboratory.

Under Fredkin's free rein, Gunkel soon switched his research from artificial

intelligence to a comprehensive study of the brain. In typical Gunkel

fashion, he bought five hundred of the best books in existence on the brain

and read half of them cover to cover. Then he set out to summarize

all

the findings, and to synthesize and "transcend" them. Though

Gunkel considers the book that resulted from his research his greatest

accomplishment to date, it was never published. Fredkin agrees that

the work had considerable merit. But he explains, "Unfortunately, publishers

are not interested in the works of mavericks outside the system, no matter

how brilliant."

Fredkin further laments, "It weighs on me that Patrick has had to work with so little support for so long." Subsisting for years near the poverty level, Gunkel says he doesn't mind his low income, except as it affects his work. He is thankful he has managed to get enough support from friends and institution through the years to study whatever he wanted. However, with no degrees, no published work, and no savings, he worries that he could be out on the street and ideonomy stopped in its tracks when the Lounsbery grant is over in 1989. But recent developments give him hope that ideonomy may soon take off and his problems finding support could be over.

The developments are the result of a recent article about Gunkel in

the WALL STREET JOURNAL. "June 1st, 1987 will go down in history,"

he laughs, "as the day a West German landed in Red Square and Patrick Gunkel

landed on the first page of the WALL STREET JOURNAL. "Broadcasters

and publishers across the country are suddenly requesting interviews.

(Austinites got a chance to

see Gunkel and his charts one evening in July on KTVV News.)

The most promising contact has been with a major computer company that

has approached him on the possibility of developing ideonomic software.

The software could lead to the future that Gunkel envisions. Ideonomic

calculators will operate on ideas the way pocket calculators now operate

on numbers. The school child without an idea processor to help with

homework, term papers, and class discussions will be at a disadvantage.

Similarly,

ideaware will be indispensable in corporation board rooms and science

laboratories, where, to name just a few items from Gunkel's list, it could

ask questions, suggest answers, extend perceptions, and suggest areas of

research.

It could take a sentence, a paragraph, or an entire encyclopedia and

amplify it into myriads of other possibilities. According to Gunkel,

ideonomic software will be like a "gigantic microscope for magnifying the

ideocosm, revealing what is now invisible. You'll be able to get

into the universe of

ideas and see its anatomy and extract things out of it."

Gunkel believes that it's just a matter of time until there's an ideonomic

institute. The institute will train people to use and create ideonomy

and to start applying it to various fields. Through the institute,

people around the country will be able to generate and hone ideas by plugging

in to "the world's

first user-evolved computer network." As they use the network,

they will automatically contribute to its growth as well. A publishing

house will produce books from the results of all this creativity, including

an encyclopedia of concepts, an atlas of shapes, an improved thesaurus,

a catalog

of astronomical phenomena. . .

Though Gunkel claims to be more interested in the fate of the world than that of the U.S., he talks of ideonomy's ability to lead to a "stupendous renewal of American industry and science. In the future, in addition to goods, we will be manufacturing discoveries, technologies, knowledge - in short, ideas. I believe that the country will inevitably go in that direction. Ideonomy and artificial intelligence are just the tools for taking us there."

"As just one example," Gunkel continues excitedly, "the U.S. could become

a tremendous chef for the world. We could design all these new types

of food. We eat 80,000 meals in a lifetime, but all the stuff is repetitive.

With ideonomy, we can make new combinations. Each meal can be different

and

interesting in new ways. With ideonomy we can design new kinds

of clothing, houses, furniture, dogs, flowers, dance movements - an astronomical

number of things!"

Gunkel is aware that his ideas seem "absurdly utopian," as he himself

puts it. In the book on ideonomy he is writing, he has included an

epilogue replying to skepticism. He answers his own list of 21 probable

objections concerning the feasibility, importance, nature, and aspirations

of ideonomy.

Many readers may remain unconvinced.

Gunkel believes that eventually the importance of ideonomy will be apparent.

Once others begin working on its development, it could grow at an extraordinary

rate, he says. "Look at artificial intelligence. Just ten years

ago, it was rather esoteric and small scale. Before that, it seemed

absurd. Now it's big stuff."

While waiting for some concrete proof of what ideonomy can do, some

may adopt the attitude of Barry Hershey, a long-time friend of Gunkel's.

Hershey, an insurance company CEO as well as a film-maker, says, "When

I think of Gunkel's theory of ideonomy, I often think of Darwin's theory

of evolution. If we had lived in Darwin's time and had never heard of his

ideas, because they weren't yet part of the general culture, most of us

wouldn't have had an inkling of their great importance."